|

Comedy with bite, farce with an edge, a great night out after so long away from live theatre.

Only Alan Ayckbourn can make me writhe with embarrassed laughter — and recognition — with each turn of phrase and plot. ‘Absurd Person Singular’, written in 1972, presents us with three consecutive Christmas Eves and three of the couples from whose social pretentions, misogyny and sheer mutual incomprehension Ayckbourn has so often derived farce and ironic tragi-comedy. Christmas Eve — the kitchen of Jane and Sidney Hopcraft (Felicity Houlbrooke and Paul Sandys) is the control room of Sidney’s strategic cocktail party, which should set him on the path to financial success, from the low base of his small corner shop. He is the commander and Jane the cringing subordinate responsible for all practical arrangements. ‘Don’t let me down, Jane’ is his bullying refrain. Jane struggles farcically to cope with the pressures of ‘keeping up appearances’ while entertaining social ‘betters’ on whom their ambitions depend. Timid, humiliated and scorned, she develops in the final act to become, literally, a gleeful echo of her husband. Paul Sandys as Sidney brings out all the nastiness and amorality of the character whom we will experience with amused horror in the last act. In the Hopcrafts’ kitchen we meet Eva and Geoffrey Jackson, clearly not in control of their lives. Geoffrey is amoral and ambitious, played with flexible ease by John Dorney. Eva (Helen Keely) is broken by Geoffrey’s womanising and, as we later see, desperate for affection from her selfish, facile, drunken husband. By the third act we understand that she is now the stronger of the two. In between, her breakdown is played for laughs — she sits traumatised trying to compose suicide notes while the other couples acknowledge her only with conventional noises, talking and pursuing their own lines of thought and action in parallel with each other, everyone disconnected. Great ensemble acting as a kind of temporary teamwork is orchestrated by the ostensibly weak Hopcrafts. By Act 3 we’re starting to understand the plight of Ronald Brewster-Wright and his wife Marian (Roseanna Miles). He’s ably played by Graham O’Mara as the least obnoxious of the play’s characters, mystified and confused by his relationships with women. Marian, a patronising snob, becomes a helpless drunk; I found myself worrying for her as the Hopcrafts become winners and avengers, calling the tune in the social game Ayckbourn sets up for his characters. This is comedy with an edge. Despite the many moments of sheer farce, if we didn’t laugh so much we might cry for the characters in this parable.

0 Comments

Comedy with bite, farce with an edge, a great night out after so long away from live theatre.

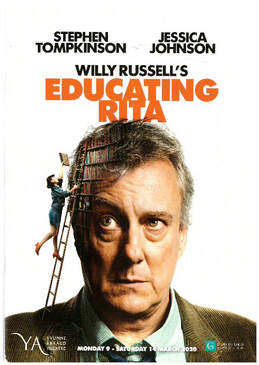

Only Alan Ayckbourn can make me writhe with embarrassed laughter — and recognition — with each turn of phrase and plot. ‘Absurd Person Singular’, written in 1972, presents us with three consecutive Christmas Eves and three of the couples from whose social pretentions, misogyny and sheer mutual incomprehension Ayckbourn has so often derived farce and ironic tragi-comedy. Christmas Eve — the kitchen of Jane and Sidney Hopcraft (Felicity Houlbrooke and Paul Sandys) is the control room of Sidney’s strategic cocktail party, which should set him on the path to financial success, from the low base of his small corner shop. He is the commander and Jane the cringing subordinate responsible for all practical arrangements. ‘Don’t let me down, Jane’ is his bullying refrain. Jane struggles farcically to cope with the pressures of ‘keeping up appearances’ while entertaining social ‘betters’ on whom their ambitions depend. Timid, humiliated and scorned, she develops in the final act to become, literally, a gleeful echo of her husband. Paul Sandys as Sidney brings out all the nastiness and amorality of the character whom we will experience with amused horror in the last act. In the Hopcrafts’ kitchen we meet Eva and Geoffrey Jackson, clearly not in control of their lives. Geoffrey is amoral and ambitious, played with flexible ease by John Dorney. Eva (Helen Keely) is broken by Geoffrey’s womanising and, as we later see, desperate for affection from her selfish, facile, drunken husband. By the third act we understand that she is now the stronger of the two. In between, her breakdown is played for laughs — she sits traumatised trying to compose suicide notes while the other couples acknowledge her only with conventional noises, talking and pursuing their own lines of thought and action in parallel with each other, everyone disconnected. Great ensemble acting as a kind of temporary teamwork is orchestrated by the ostensibly weak Hopcrafts. By Act 3 we’re starting to understand the plight of Ronald Brewster-Wright and his wife Marian (Roseanna Miles). He’s ably played by Graham O’Mara as the least obnoxious of the play’s characters, mystified and confused by his relationships with women. Marian, a patronising snob, becomes a helpless drunk; I found myself worrying for her as the Hopcrafts become winners and avengers, calling the tune in the social game Ayckbourn sets up for his characters. This is comedy with an edge. Despite the many moments of sheer farce, if we didn’t laugh so much we might cry for the characters in this social parable. The original stage play of ‘Educating Rita’ (1980) is a brilliant two-hander. There may have been some in the audience at the Yvonne Arnaud who expected to see a clone of the excellent 1983 movie of the play (I sat next to one such person) but to adapt the script for the cinema Willy Russell included 20 extra characters, who are present in the theatre script but not onstage. The dialogue between Frank and Rita conjures up the situation between them and the social conditions outside the study where they speak with poignant and sometimes highly comic effect. This is wonderful writing.

The scene is the room in a respected university where Frank, a middle-aged professor of English, meets with Rita, a young Liverpudlian hairdresser who has applied to follow an Open University course. Rita wants to “know everything” and so to move her life out of the track in which she feels her family and social class have trapped her from birth. Their relationship swings back and forth in “snapshots” of their successive meetings. His wonder and somewhat patronising perception of her naïve and emotional responses to the books the course demands her to read, and her awe for his middle-class academic world, give way to a more complex relationship as she begins to see herself as “educated.” This is a sparkling comedy as well as an exploration of class and gender conflicts. It’s full of wit and irony from both student and professor: Rita’s sharp Liverpudlian humour bubbles and sparks in every scene, while Frank’s ironic view of himself and his own weaknesses is a great foil for her edgy, nervous self-deprecation. The process of educating Rita changes the lives of both, in ways that finally remain open to the audience’s speculation. And so the cast of two are onstage for the duration of the play, and in this production they seem to me to bear that responsibility admirably. Stephen Tomlinson is not Michael Caine and makes no attempt to emulate him. He is the cynical, tired lecturer who has found himself divorced from his first love of literature; he glimpses in the uneducated, raw reactions of Rita a charm and honesty that the students who come to him through the traditional education system learn to suppress, in favour of learned responses from ‘recognised sources’. Jessica Johnson is Rita, spontaneously affectionate, easily overawed but made gradually confident, above all by mixing with other students at the OU Summer School which is part of her course. Her stage presence is joyfully active, veering from literally bouncy when Rita is happy, to angrily sullen when she feels put down, so that her physical equilibrium at the end of the play tells its story. The play was written forty years ago, yet it hasn’t dated. The English class system remains rooted in 2020 as in 1980 and academic mores also endure. And in spite of advances in gender equality, many women’s options remain as limited as Rita’s, without a conventional education. This review was originally published in Essential Surrey Magazine https://www.essentialsurrey.co.uk/theatre-arts/theatre-reviews/educating-rita-review/ Book Review: What I heard on the Last Cassette Player in the World by Ben Ray (Indigo Dreams)17/12/2019 What I heard on the Last Cassette Player in the World

Ben Ray (Indigo Dreams) Ben Ray’s second collection is a medley of experimental poems alongside absurd, surreal propositions apparently thrown out ad lib, and sincerely felt and expressed meditations on political, environmental and existential themes. He is a master of the sustained metaphor, as in ‘The day they decimalised the words.’ He plays with the historical event of currency decimalisation in Britain in 1971, showing how cultural change impinges on meaning. With the currency of old words suddenly devalued, the elderly struggle to adjust, are confused and disenfranchised: “The older generation, they didn’t understand – they cried when they opened their mouths and their old, familiar sounds wouldn’t work.” And even young people feel a “nagging, empty sadness / for everything that had been left unsaid” and the “now-strange symbols” they see when they find old words “tucked in between the leaves of books / or carefully hidden on stained shopping lists.” Foreign places and past times inspire other poems that deal with change. In a sequence entitled ‘A short guide to Sengoku period Japanese pottery’ Ray follows the violent evolution of Korean pottery into traditional Japanese porcelain design through the enforced abduction of 20,000 Korean craftsmen and artisans by the Japanese, in the Ceramic Wars of 1592 –1598. This is a very beautiful poem, with the understated grace of an oriental art work. An artisan tells of the violent uprooting of their life in stanzas named for the processes of their craft: ‘Throwing’; ‘Centring; Opening up’; ‘Firing’; Glazing’; ‘The finish’. In ‘Throwing’, the opening stanza, the narrator. totally in tune with their art, describes how “When first placed on the wheel of Korea / I was thrown most delicately”: “clay ran like love in my family’s veins.” In ‘Centring’ the war approaches until there are “soldiers/ wading through shards of villages.” The potters’ disturbance in their work is ironically shown: “When you make a bowl and you are briefly distracted by, say, a dog in the workshop or the murder of one’s mother…” And so the story goes on: “Twenty thousand pieces taken from their home / is a rape, a murder.” The Korean craftsmen were taken “in the hope that some of us could be reshaped /and learn to echo the contours of this strange new island.” The assimilation is almost completed, as the pot is fired and glazed: “The longer a pot is dipped in the glaze / the more the colour settles,/melting into grooves now familiar.” “And now, here we are not quite Kinsugi but nearly there – the shine on us has set hard…” The narrator keeps his pride as an individual artist, however: the ceramics are now exported globally as traditional Japanese art but the narrator insists: “I like to think that they were not born of Korea or of Japan but of us…” Welsh places have inspired some of the best poems in the collection. One is another sequence: “Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal”. In six segments Ray maps the changing nature of the canal and its banks in engaging detail, from its beginning “poured out of the Brecon basin in a feisty swirling shaking liquid rush” until in stanza 6: “Like all empires, the canal does not lead to glory it leads to obscurity and silence and rubble…” ‘The Landsker Line’ plays with “the distinct linguistic and cultural boundary between the Welsh-speaking areas of northern Pembrokeshire and the English-speaking areas of southern Pembrokeshire.” (Ray’s epigraph) This is not about the landscape, but a map of the dialects that remain as traces of historical skirmishes, military and linguistic, between the English and the Welsh cultures: “Brandy Brook an anglicised battle line the next beach north a fighting statement: Pen-y-cwm. To trace it you will need a phrasebook and the voice of your grandfather time clots and cloys in the breaths between sentences.” “Morning After” carries a cynical epigraph from Rainer Maria Rilke about the city of Rome. In Ray’s response, the extant remnants of the Roman Empire are redrawn as the features of an aged actress, irrelevant to the present day, though still demanding attention: “Time, the great undresser, long ago got wise to your amphitheatrics and confiscated your frescoed chic – left with mosaic rashes, like old tattoos…” Ray’s enjoyment of sounds and mild punning is in the rhyming of “amphitheatrics” with “mosaic rashes” – it works for me in this poem. though not in all. Not beyond politics and environmental themes, but encompassing them, the narrator’s personal memories leaven the collection: I enjoy ‘Hay Bluff’, a memory of a climb with his father to look down over the River Wye; ‘The Gift’, a memory of his father’s humanity; the bleak “Winter at the Sands Café, Newgale. In “Some Other England”, a memory of Morris dancers (“Morris with a darker touch,/ faces that interchange like birds in flight”) who seem to “solve this internal conflict / and reach into some other England” picks up again the dominant theme in this varied collection: the fall of empires and how human beings adapt to cultural change. Janice Dempsey December 2019 First published on https://www.writeoutloud.net/public/blogentry.php?blogentryid=97913 “Ten Times Table” by Alan Ayckbourn

Yvonne Arnaud Theatre 3 stars I laughed a lot! This ‘romp’ takes a side-swipe at extremes of class and politics, highly relevant today. As a huge fan of Alan Ayckbourn’s plays, I came to “Ten Times Table” expecting surprises, wit and playful baiting of the English class system. The play’s scenario is perfect for that: a self-appointed committee in a small English town, planning a ‘festival’ to celebrate an 18th century local confrontation between land-owners and land-workers. Over the course of their weekly meetings the team-work their optimistic, peace-making chairman hoped for falls into chaos and farce ensues. (I assume that the title of the play refers to their ten meetings round the table in the dilapidated ballroom of the Swan Hotel.) The cast of characters is pure Ayckbourn: the fussy, pedantic ex-lawyer Ray (Robert Daws); Eric, the weak “lefty” school teacher with a chip on his shoulder (Craig Gazey); Lawrence, the drunken businessman with a failing business and a breaking marriage (Robert Duncan); Helen the Thatcher-like virago, (Deborah Grant); young, susceptible Sophie (Gemma Oaten) and Philippa (Rhiannon Handy), and the chirpy, peace-making chairman of the committee, Donald (Mark Curry). Add to this list Audrey (Elizabeth Power), the ancient deaf lady assigned to take minutes, and Tim (Harry Gostelow) the aggressive right-wing ex-military farmer who’s co-opted to move the planning forward when the committee’s stymied as such committees often are, and the stage is set for the confrontations of politics and class that Ayckbourn uses to poke fun at all the stereotypical views of his caricatures. Some of the funniest moments of the play are provided by Mark Curry as the hapless chairman of this dysfunctional committee. His balletic body-language and almost operatic delivery of attempts at reconciliation between warring committee members are brilliant – “We-e-e-e-e-ll … no-o-o-o-w!” Elizabeth Powers as Audrey is also a delight: necessarily side-lined by deafness, her attempts to understand what’s going on are touching, familiar and funny. I enjoyed the evening and laughed a lot. I did feel that the play itself was a little static visually, until the last scene presented the farcical outcome of the deliberations of the committee. That said, the performances of all the cast were suitably exaggerated, in keeping with the author’s evident aim of presenting the characters’ stereotypical responses to the situation and to each other, so the pace didn’t drag. Alan Ayckbourn says of this play, “In more innocent days, it would probably have been subtitled a romp”. First performed in January 1977, with Margaret Thatcher poised to become Prime Minister three years on and several years of social and union unrest behind, Ayckbourn takes a sideways swipe at both ends of the political spectrum and all levels of the English class system, positioning himself as “the man in the middle” of the chaos. And yes, it is a romp! Janice Dempsey “The Lovely Bones” based on the novel by Alice Sebold.

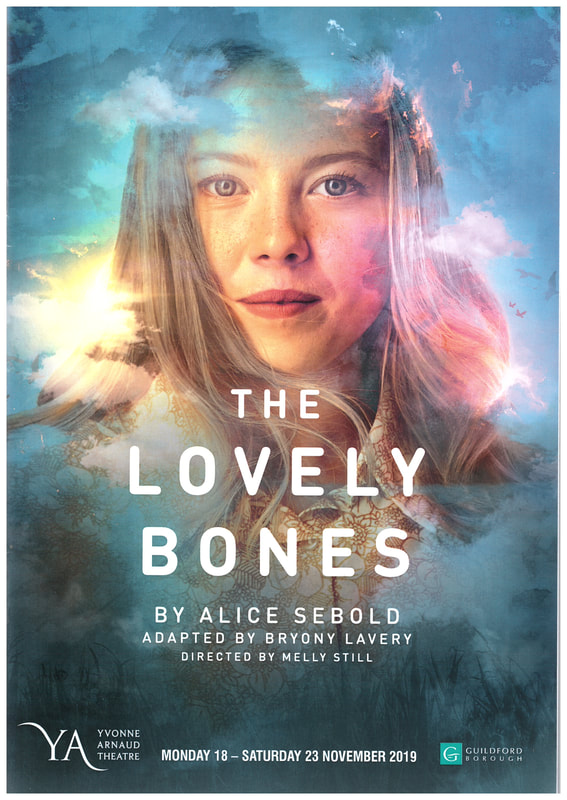

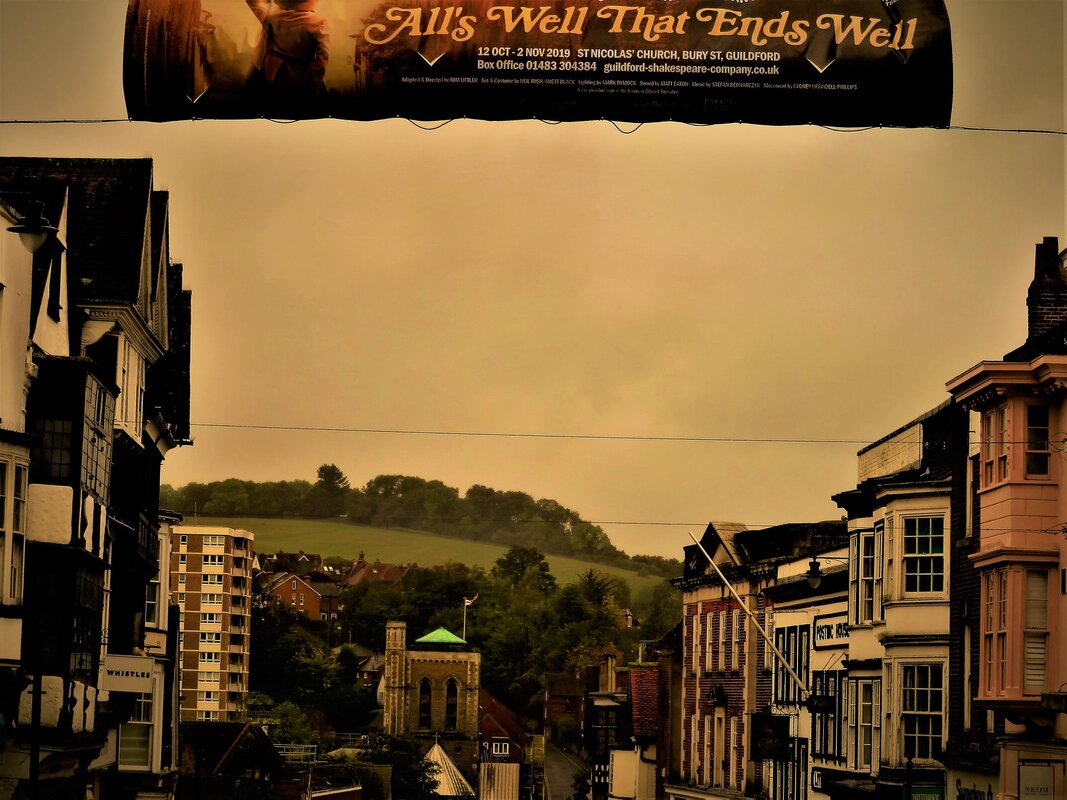

A wonderful life-affirming evening. Charlotte Beaumont is the teenager from heaven! It’s not often that I feel that an adaptation of a book I’ve enjoyed has gained a lot in the process of adaptation for the stage, but at the end of the first half of “The Lovely Bones” that’s just what I was telling myself. This is a highly inventive, imaginatively conceived, beautifully staged production. The story is of the unsolved rape and murder of a fourteen-year-old girl by a serial killer. As in the novel, it’s told by the victim herself, who’s looking for release from the unfinished business that her violent early death has left. She haunts the people from her short life and place where she was killed, trying to make them find her murderer. But this is no ordinary ghost story. Susie (Charlotte Beaumont) is a feisty young teenager with all the energy, capriciousness, love of fun, music, dancing, and awareness of boys, typical of living girls of fourteen. Her pleasure when things go right is expressed in dancing and radiant smiles; her frustration at being unseen and unheard brings hissy-fits and glowering pouts, when things go wrong; she’s as impulsive, brave and strong-willed in death as in life. Charlotte Beaumont is perfectly cast: utterly charming, she moves the story on with joy, humour and verve (there’s a lot of laughter in this play.) In the second half, when the focus of the play moves to relationships within Susie’s grieving family and among her old friends, now maturing adults, the pace slows somewhat. Fanta Barrie as Lindsey, Susie’s gifted younger sister, gives the role moving depth as, still grieving, she develops and matures. Their father, Jack (Jack Sandle) is obsessed by the need to find the killer. In grief her mother Abigail (Catrin Aaron) is desperate to keep the rest of her family together by returning to “normal” life but Jack’s obsession drives her to leave him. Meanwhile, the psychopath, Harvey (Nicholas Khan), remains totally unforgivable – no extenuating circumstances are suggested for his appalling crimes. He is a weak, unhappy man who excites no sympathy: we’re as relieved as Susie when his fate catches up with him. This play is comparable with “The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night Time” for originality. The staging is remarkable. Using a huge reflective surface extended above and semi-transparent layers behind it, space becomes multi-dimensional. Susie is “trapped” in heaven with a caring “transitioning officer” guiding her but she’s still with her family and friends on earth, though she can only watch as they grieve and develop their relationships without her. This aspect of the story could become mawkish, but it’s saved from over-sentimentality by the vigour of the writing and acting, as well as by the wonderful evocation of a meld of heaven and earth and different kinds of time enacted simultaneously: Susie’s “transition guide” points out that “on earth their time is so short.” (I paraphrase.) This entertaining play lightly carries the life-affirming message that lives must be lived, that grief must be borne and that we must play the cards we’re dealt, however hard or unfair they seem. For Susie, her spirit moves on when she learns and understands the life and people she lost on earth. I thoroughly recommend “The Lovely Bones”, both this play and the book. All's Well that Ends Well – the Guildford Shakespeare Company at St Nicholas Church, Guildford.23/10/2019 Wonderful theatre, in Guildford pre-West End. I can’t praise this production highly enough – Shakespeare at his most accessible, entertaining and thought-provoking. Hannah Morrish's performance as Helena was a triumph. Enjoy the GSC's unique interpretation of Shakespeare in the beautiful setting of St Nicholas Church, Bury Street, Guildford (the church with the green roof across the bridge at the bottom of the High Street, in this picture.) 13th October – November 2nd 2019 By the end of the first scene of the GSC’s production of “All’s Well that Ends Well” we knew that we were enjoying the work of a first-class team: the adaptation, set, beautifully integrated musical arrangements and above all the actors all operating at a high level of excellence. This is one of Shakespeare’s ‘problem plays’, which leave the audience with unresolved issues allowing directors to interpret its meanings creatively. David Littler, the director of this production, has taken up the challenge magnificently.

The story is about love, honour, betrayal, lies, trickery, and the mix of goodness and weakness that makes up the human soul. There’s a buffoon (Parolles) who makes us laugh and is punished for his shallow boasting and weak character. There are fairy tale tropes – rings that unravel a deception; a low-born character who receives a high-born marriage partner as a reward from a ruler. But in this story the low-born is female: Helena, a deceased doctor’s daughter, who falls in love with Bertram, the son of her guardian, Countess Roussillon. The Countess loves Helena as her own daughter. Bertram, conscious of his own inherited status, rejects Helena on the grounds that she’s beneath him, and goes off to Paris to fulfil his social role as a gentleman. When Helena goes to Paris too, with a successful cure for the dying French Queen (a gender reversal from the original), she is rewarded by being told to pick one of three marriage partners, and of course she chooses the reluctant Bertram. He is furious and refuses to consummate the marriage into which he is forced by the Queen. He leaves the court next day with his friend Parolles, to join an army against insurgents. He writes to Helena telling her that she will never be his wife until she wears his ring and carries his child. Since he is staying away from her, this seems impossible. But Helena is resourceful and single-minded, and with the help of Diana, a young virgin, tricks Bertram into unwittingly consummating their marriage, rendering it an unbreakable social and legal bond. The dénouement is a win for Helena, but we are left in some doubt how happy the marriage may turn out to be in the long run. Her most rewarding relationships seem, in this production, to be with the three female characters who have supported her plans: the Countess, now a loving mother-in-law; the Queen; and Diana, the virgin who helped her to snare Bertram. We wonder, has all really ended well? Hannah Morrish as Helena brings to the part all the nuances of love, fear, disappointment, joy and hope that the complex narrative demands. Her delivery of Shakespeare’s lines render them her own, as comprehensible to our modern ears as they were to the Elizabethans’. Robert Mountford’s interpretation of Parolles is a delight: a leggy, round-eyed, flamboyantly expressive character who can puff up with braggart’s pride and deflate comically with fear or humiliation next second, when confronted. Miranda Foster plays the Queen with tremendous spirit and the Countess with all the warmth that one would wish for in such a loving mother-in-law. The music must be mentioned: the theme from Fleetwood Mac’s “The Chain” in the original and as a piano theme running through the play; Patti Smith; Joni Mitchell, and Chrissie MacFee’s beautiful “The Songbird” stay in my memory of this enchanting evening. This review is also on Essential Surrey's Reviews page https://www.essentialsurrey.co.uk/theatre-arts/alls-well-ends-well-review/ Open Air Theatre by the GuildburysThis fast-paced comedy is another triumph for the Guildburys – brilliant individual and ensemble acting and wonderful comic timing. Ian Nichols and the Guildburys continue their record of choosing high quality, brilliantly entertaining plays for their summer season of open-air theatre. Alistair Beaton's adaptation of Nikolai Gogol's The Government Inspector still carries a punch today, 180 years after it was first staged in Tsar Nicolas I's authoritarian Russia. Civil servants and provincial officials are mercilessly lampooned, to hilarious effect. Satirical, farcical and cynical, it was nevertheless read and admired by the Tsar himself. The story has no heroes. Khlestakov is a foppish, conceited young man who is travelling Russia with his servant Osip, wasting his father's money, gambling and drinking. They find themselves stranded in a town inn, without money or credit. The Mayor of the town is seized by the idea that this stranger is a high-ranking inspector from central government, come to find out what he and his deputies have been doing. He is fully aware that he is guilty of extortion, wasting public funds and mistreating the townspeople he should be serving, The Postmistress, Commissioner for Health, Magistrate, Superintendent of Police, Director of Education and Doctor are equally terrified. To protect them all, the Mayor insists that Khlestakov and Osip stay with his own family, plies Khlestakov with vodka and flatters him until he feels so important that he almost believes that he is indeed a powerful man from Petersburg. He's quick to realise the opportunities for making money, too, accepting "loans" that the guilty dignitories offer him (all except the Superintendent of Police who has his standards to keep up – he only takes bribes, never gives them!) The dénouement is a masterpiece of comic choreography: I won't spoil it by revealing all.

We laugh delightedly at the jokes and wonderful clowning. But we also hear subtle echoes of the threat of the collapse of responsible government and shortage of honest, reliable leaders on a national scale, today. Photos by Phill Griffith This review was first published in Essential Surey Magazine https://www.essentialsurrey.co.uk/events/the-government-inspector-review/

What would have happened if Romeo had woken up a few minutes earlier at the end of Shakespeare’s tragedy and the ‘star-cross’d lovers’ had survived? How would the fourteen-year-olds’ romantic dream have stood up to the test of time, ageing and the stresses and routines of married life? Ephraim Kishon’s play, brought to the Electric Theatre stage this week by the Guildburys, sees the situation thirty years after their survival: Juliet as a discontented, frustrated wife and Romeo a seedy middle-aged husband with money worries and mother-in-law problems, battling with each other over the disappointments and disillusionment of it all. And who do they blame? The author, literally, of their troubles: William Shakespeare himself! That’s where it gets surreal, for Will himself is haunting them. Written as iconic romantic lovers, now they’re locked in an archetypal marital conflict. Only Will can solve their problems and he’s much more interested in strutting like a peacock, declaiming in blank verse (unlike the rest of the characters, he’s forgotten how to speak prose except at moments of great stress), and attempting to seduce their own fourteen-year-old daughter, Lucrezia. Lucrezia, a modern “daughter from hell” is totally up for it; according to Juliet’s old Nurse, now a friend of the family, she takes after her mother Juliet at that age! This a rumbustious take on Shakespeare, and incidentally a romp through the text of several plays. Friar Lawrence is senile and keeps thinking he’s in ‘Hamlet’ and Shakespeare himself is prone to declaiming from Macbeth, Julius Caesar and the history plays, in his conversations with the unhappy couple. We’re the groundlings, and at one moment the Bard invites our questions – so you might want to come to the play with an inquiry he can answer from the grave – for instance, who did he leave his very best bed to? As always, the Guildburys have brought all their enthusiasm and dramatic skills to bear on this production, directed by Steffen Zschaler. Jonathan Constant is a wryly humorous, hen-pecked Romeo, harried by Danielle Buckett, his shrill, disillusioned Juliet, in scenes of marital discord that may strike a chord with many middle-aged couples. But their mutual support against Shakespeare also rings true. After all, they’re in the position of discontented children complaining to a parent, ‘I didn’t ask to be born!’ Ian McShee as the preening ghost of Shakespeare is brilliant. His dancing, self-congratulatory body language and swift changes of oral tone and register are a delight. Tuuli Albekogliu is Lucrezia, a tall streak of defiance who transmutes to a capricious temptress when Shakespeare is about. Tina Wareham gives a memorable, humorous and professional performance as the old Nurse, and Graham Russell-Price’s interpretation (in faux-Irish) of Friar Lawrence in our “Me Too” age is very funny. And Tautvydas Kuiiesius, the guitarist, deserves an accolade for his amazing cockerel impersonations! This satire was written after Kishon had survived Nazi concentration camps in Poland, and three marriages. He clearly learned much in his long life – above all, how to laugh! This review was first published online at www.essentialsurrey.co.uk/theatre

This brilliant play was at the Yvonne Arnaud Theatre, Guildford, in the week beginning 12th March 2019 and my review of it appeared in Essential Surrey magazine that week.

We’re all aboard the SS Italian Castle for an evening of outrageous overacting, hilarious sight-gags, running gags, puns and misleading conversations sparklingly interwoven in the masterly way that fans will recognise from other Tom Stoppard comedies. This is a pastiche of musical comedy that really works. The story is based on a play by the Hungarian playwright Ferenc Moulnar, “The Play’s the Thing”. In Stoppard’s version two playwrights and three of the cast of the play they’re writing are all cooped up together on a liner crossing from Cherbourg to New York, trying to complete the script. But a love triangle involving the leading man, the leading lady and the pianist is constantly interfering with the progress of the plot they’re trying to finalise. Enter Dvornichek, the cabin steward (Charlie Stemp) who is quickly renamed by Turai (John Partridge) and Gal (Matthew Cottle) the writers, and becomes the character who explains all the details of the present situation onstage, for our benefit, as if the action so far hasn’t made it clear enough. Gradually the writers’ power over their play becomes shared, and then taken over, by the rest of the characters: Natasha, the passionate female lead and ex-lover of Ivor Fish (Simon Dutton), Adam (Bob Ostlere) her present fiancé and Dvornichek, now called Murphy the Irish policeman for the purposes of the play within the play. In the tradition of all musical comedies of the first half of the twentieth century, all the knots, both among the characters and in Turai’s play, are satisfactorily untangled and the evening ends with some spectacular dancing by Charlie Stemp and John Partridge, and an unexpected musical performance by Issy van Randwyck as Natasha. The set is dazzling: we could almost smell the sea air. The costumes and dancing are a delight, the songs and dance routines are beautifully and satirically performed. The whole cast delivers Stoppard’s intricate counterpointed dialogues, full of wordplay and misunderstandings, with perfect dramatic timing. The running jokes are irresistibly funny: the steward, new to the sea-board life, is mysteriously staggering to a ship’s roll when the SS Italian Castle is in dock, yet in a storm he stands steady as a rock while the passengers are being thrown helplessly around the deck. And we wonder, will Turai ever actually be served with the brandy he keeps ordering and that Dvornichek keeps faithfully bringing? (No spoilers for that running gag.) It’s no surprise to read later that in 1953 PG Wodehouse also created a version of Moulnar’s 1926 play, setting it in a castle, with Dvornichek a Jeeves-like butler. Stoppard’s 1984 version has the same appeal as Wodehouse, and this slick comedy hasn’t lost any of its appeal in the twenty-first century. For an evening of fun and laughter, don’t miss it! FIVE STARS Janice Dempsey 12/3/19 |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed