Bullying, insults, extortion of confessions through fear and betrayal of trust, all are timeless techniques employed by the powerful in a society divided by inequality. The politics of gender, money, power and religion were equally responsible for the severing of Anne Boleyn’s head from her body, as the sword that cut through that “little neck”. Sarah Gibbons is a beautiful, charismatic Anne who develops from a wilful teenager of nineteen into a focussed young woman who prizes her own honesty and perseverance above all, holding her own among the bullying men who rule Henry VII’s court. Her cowed and fearful female friends betray her despite their love for her, when they're beaten and threatened with torture. "I want to stay alive", moans Lady Rochford (Claire Rackleyft) to Anne afterwards.

As far as the status of independent-minded women is concerned, nothing has changed in James's time. But does he intend to use his autocratic power in a new way that will bring the country together? Has Anne’s attempt to promote Protestantism changed the balance of power in religion? Did James’s English translation of the Bible based on all the disputing factions in the English church heal the rifts he (and Anne before him) saw in British society? James's dealings with the clergy verge on torture: they're locked in a room for hours without food or drink, and expected to "sort it out among themselves". They emerge, weakened, but standing fast in opposition to any attempt to make worship more "democratic": there must always be a barrier between the elite clergy and the congregation. The absurdity of the scene where altar-rails are seen as a vital matter on which there can be no compromise or agreement is only in the minds of us, the future audience. As Anne says, the “demons of the past” wouldn’t recognise the minds that we, “demons of the future”, bring to the questions this play asks. And Howard Brenton doesn’t pretend to offer answers, other than Anne’s simple prayer for kindness.

0 Comments

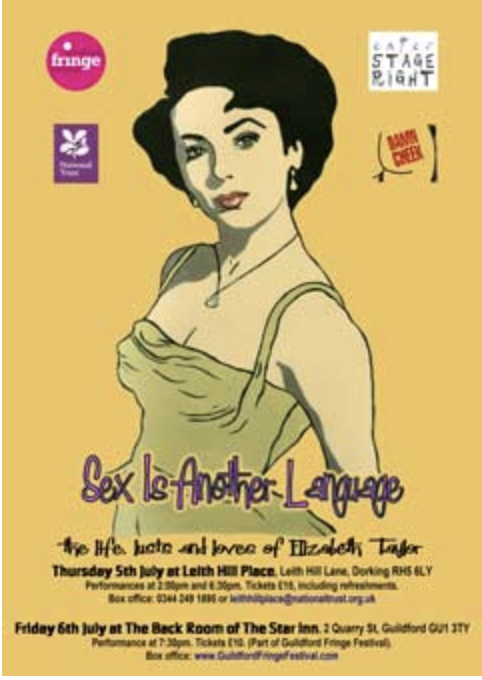

Not that this is a depressing account of Elizabeth Taylor’s chaotic life. Over and over again humour breaks through after the most intense moments, as Taylor proudly gathers up her strength and presses on along the turbulent path that she has chosen. Glorying in her sexual magnetism, unashamedly hedonistic, she commands the stage, And yet this is not a portrait of a stereotypical diva. The performance at Leith Hill Place was intimate and close-up: we sat a few feet away and through Claire Malcomson's intense recreation of Taylor were introduced gradually to the complex, warm human being as well as to the larger-than-life, dramatic personality. The production by Darren Cheek and Tony Earnshaw (Damn Cheek Productions) is a tightly choreographed and disciplined 70 minutes with no break. Music is in the air at times, redirecting to another era, another filmset, another place, a change of mood. The pace is excellent and uninterrupted by scene or costume changes. Claire Malcolmson's rich and nuanced performance provides all that's needed beyond a chair, a nightstand and a drinks trolley. We meet Elizabeth Taylor in middle age, distraught and wailing for a drink after losing the love of her life. She looks back on her journey from early child-stardom in “National Velvet”, through six marriages before the age of thirty-two, a glamorous Hollywood career, a spiral into addiction, cure and relapse. She speaks directly to us, sometimes as “all of you out there”, but more often as “Michael”. Listening to her memories and reliving her highs and lows, we deputise for Michael Jackson, whom Taylor recognised as a kindred spirit, equally damaged by an unhappy childhood and equally ready to use his wealth to escape into “Neverland”. Their strange relationship became legendary after the death of her other soul-mate, Richard Burton. But it seems to be Mike Todd, the father of her children, whose death she’s mourning in her opening lines. “Sex is what drives us, friendship is what rescues us,” says Elizabeth. We learn that not all her relationships with men were based on sexual love: in the 1980’s the death from AIDS of Rock Hudson helped her to raise awareness and fund research into its cure, and she admits that she loved him as her very dear friend, not her lover. Her long, passionate and mutually destructive relationship with Richard Burton was quite another matter. The harrowing emotional rollercoaster of it, the addiction to alcohol and drugs that accompanied it and her grief at his death brought tears to my eyes. This woman who was in films as a child actress (“I never had a supporting actor with fewer than four legs till I was sixteen!”), and who felt her life circumscribed by fame, learned to use her power to help others at the last. Sex was a language she mastered, but friendship gave her life its meaning. Tony Earnshaw's well-researched and thoughtful play sheds light on this life, at once so successful and so personally tragic. It's one more in Tony Earnshaw's oeuvre of successful plays which are launched from Surrey and have the legs to carry them on. "Doors", produced last year in Dorking, subsequently played New York for three weeks, as well as London and a national tour. "Sex is Another Language" with Claire Malcolmson has had its debut at Leith Hill and in the Guildford Fringe, and will be back in Surrey after the summer break. After that, many more audiences should see this original production. We loved it and gave it five stars without hesitaion. |

Archives

November 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed