|

‘Breaking the Code’ by Hugh Whitemore Guildbury Theatre Company at the Electric Theatre, Guildford Directed by Oliver Bruce 20th – 23rd March 2024 4 Stars A thought-provoking, emotional and moving evening at the theatre This play pays tribute to and tells the story of the tragic life of Alan Turing, the brilliant mathematician whose work at Bletchley Park broke the German Enigma machine’s code during World War II and who went on to formulate the concepts which underpin modern computer science. The tragedy centres upon his determination to live a homosexual life without pretence in British 20th century society before 1989 — to break the social code of his time. We’re presented with a portrait of a complex character, strong-willed and fiercely intelligent, whose inability to compromise with social mores brought him into conflict with convention, caused him to be labelled a security risk despite his patriotic stance, and finally interfered with his principal passion: the drive to find a way to make a machine that can ‘think’.

The topic is, of course, highly relevant to today’s world, when AI is developing in the way that Turing dreamed it might (though he could not foresee our current fears of its manipulation by bad actors) and it’s also relevant to the town of Guildford, where Turing’s family lived and he himself often stayed. There are no ‘bad actors’ in this Guildbury production (forgive the pun!). Oscar Heron as Turing gives a bravura performance. He develops the character from the frustrated schoolboy, hen-pecked by his conventional mother and hopelessly in love with Christopher, a heterosexual friend with whom he shares his excitement over the wonders of science and mathematical concepts. From there he grows to manhood as an obsessive seeker and solver of scientific problems, with an emotional life stunted by the death of Christopher while they are both at school. And after the ‘outing’ and the abuse Turing suffers at the hands of the law, his maturity and dignity, as a man who has achieved and understood much. Eleanor Shaikh as Alan’s mother traces a journey that begins in crass conventional materialism and moves into understanding and loving support for her son when he admits his sexuality to her at last. Another sensitive and moving performance, this. Mike Pennick and Lauren Phillipou, as Turing’s colleagues at Bletchley, both deliver brilliant ensemble scenes in the second act which brought tears to the eyes (and audience applause) on the night we were there. Stephen Liddle plays the detective who has the task of arresting Turing, with a sense of the regret that the law broken in secret by so many other men now has to be invoked against Turing, a sincere and intelligent person. And finally, I must also mention the striking set and the brilliantly varied musical and sonic transitions between the scenes in this, another Guildbury Theatre Company tour de force. [END: 443 words] Janice Dempsey

0 Comments

HAPPY NOW? by Lucinda Coxon'Happy Now' by Lucinda Coxon

Directed by Gilly Fick The Guildburys at The Electric Theatre 29th November to 2nd December 2023 FIVE STARS An evening of immersive, hilarious, bitter-sweet theatre in Guildford. The Guildburys Theatre Company bring Linda Coxon.’s ‘Happy Now?’ to the Electric Theatre for just four nights and we counted ourselves very privileged to be there on Wednesday 29th November, the opening night. We found ourselves following the fortunes of two well-heeled couples, parents of young children, to whom life seems to have awarded all the materials they need for happiness. But each of the marriages is on a plateau and at risk. As Kitty (efficient career woman, housekeeper and mother) warns John, her well-meaning but weak husband, at a critical, exhausted moment, ‘Something is going to happen. Something bad.’ The bad things that do happen give us two hours of witty, perceptive dialogue, moments of fellow feeling and sympathy, straightforward belly-laughs and by the end of the play the sense that we know these people and can relate to their dilemmas. None of the characters is one-dimensional; all are tragic and comic simultaneously; all seek happiness; none have found it. Even Carl, a gay man with his own romantic relationship problems, and Michael, a married sexual predator, prove to have dimensions beyond stereotypes. The cast are excellent without exception. The anchor character of the whole play, Kitty, is played by Samantha Remnant with tremendous vigour and sensitivity; we feel for her as she is emotionally buffeted by her family and her self-absorbed, insensitive mother, June (a convincing performance by Kathryn Attwood) and the expectation that she will support everyone around her at home and at work. We respect her self-control. And we laugh with her as she deals out irony and plain speaking in response to the pressure of it all. No spoilers, but there’s a seduction scene that’s absolutely surreal and hilarious! Neil James is excellently cast as the lanky, cynical, amoral Michael and Jonathan Constant plays his antithesis as John. Bea, Kitty’s neighbour and friend, is played by Claire Howes. Her marriage to Miles is threatened by his ennui and his disrespect for her. Her escape from frustration into a creative job and self-respect coincides with his collapse into alcoholism and dependence on his friends. Miles has some of the funniest lines in the play (superlatively delivered by Olly Clifford) but the clowning and cynical banter can’t disguise that he is as potentially destructive as John, who takes Kitty for granted and constantly adds to the pressure on her, and Michael, the hotel-room seducer. Carl (Tim Brown) is revealed as the most supportive character to Kitty and others; he is as vulnerable as she is, despite the strength both clearly possess. This is a brilliant play, commissioned for and first produced at the National Theatre in London. Gilly Fick’s direction and the Guildburys creative staging team and excellent actors have given us a memorable production of it here in Guildford. Don’t miss it —a few tickets are still available. https://electric.theatre/shows/happy-now/ The Canterbury Tales — Guildford Shakespeare Company

14 – 29 July 2023, The Astolat Pavilion, Stoke Park, Guildford A fun-filled, playful evening for everyone. Ever sat in a classroom feeling bored to tears by Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales? The multi-talented GSC have come up with a sparkling, hilarious antidote to memories of dry lessons: an evening of brilliant entertainment. Here in song, dance, puppetry and comic acting they tell seven of Chaucer’s pilgrims’ stories of honour rewarded and greed and vanity punished, while in the audience we’re constantly involved, consulted for our votes, and even contribute our own voices to the organised mayhem on the stage. Little or no ‘fourth wall’ here. The script is based on their 2014 show, which we saw in St Mary’s Church, but it has been updated for the open air setting of the Astolat Pavilion, and feels if anything more like a mediaeval fairground show, despite including twenty-first century electronic audio media. The telling of ‘The Miller’s Tale’, starring Rosalind Blessed, had us in fits of laughter, not only at Ms Blessed’s wonderfully comic Miller, but by the witty use of sound effects One of my favourite tales was the company’s musical version of ‘The Nun’s Priest’s Tale’ with Matt Pinches narrating as a duck who looked very much like Rod Hull’s Emu, with Chanticleer the rooster, his seven wives and a sly fox, all played by huge puppets steered and voiced by Rosalind Blessed, Will Arundell, Nikita Johal and Sarah Gobran. The hen backing-group to the songs sung by Will and Rosalind was a great invention! Will Arundell’s lovely singing voice, musical skills and flair for comic timing are great assets in his various roles, whether as a knight, a scoundrel or a rooster. Nikita Johal proved herself very versatile again — from sinuous, sexy princess, to little old woman, magician or rapacious fox, she’s full of delightful energy. Rosalind Blessed is a constant source of fun and humour and Matt Pinches, the only member of the company who was in the original 2014 show, has a fund of invention and comedy. And Sarah Gobran in red catsuit is the fifth — but not the least —star of the show — we’re so used to seeing her in breeches roles, we absolutely loved her satirical portrayal of the worldly, patronising Wife of Bath! Brought up to date and yet true to the spirit of mediaeval storytelling, this ‘Canterbury Tales’ is a masterpiece of comedy and theatrical invention. Even if you’ve never studied Chaucer, and even if you’re a Chaucer scholar, and whatever your age, you will love this show. Janice Dempsey 18th July 2023 This review was first published online in Essential Surrey ‘Henry V’ by William Shakespeare. Adapted by Caroline Devlin The Guildford Shakespeare Company 15th June – 29th July 2023 A brilliant adaptation —a vigorous, fast-paced history of the battle royal at Agincourt, in the gothic shadow of Guilford Cathedral. Theatre at its best. Can this cockpit hold The vasty fields of France? or may we cram Within this wooden O, the very casques That did affright the air at Agincourt? [Henry V, The Prologue] The stage that the Guildford Shakespeare Company have erected at Guildford Cathedral this summer certainly can bring to life this patriotic English play. With a cast of only five actors, who play 32 different parts between them, this is a brilliant adaptation: fast-paced, clear story-telling, spiced with humour and thought-provoking observations about leadership in war and peace. Briefly, the plot concerns the newly-crowned King Henry V who as a young prince has earned a reputation as a tearway, but who now intends to take on his responsibilities as king. Insulted by the Dauphin of France because of his recent past behaviour he is enraged and decides to take action to regain control of land Britain owns in France, travels across to France with a small army and seizes the town of Harfleur. The huge French army engages with them and, despite all odds, at the famous battle of Agincourt the French capitulate and a peace treaty is negotiated. As always, GSC have utilised the venue to enhance the production. The gothic style of Guildford Cathedral’s exterior becomes in turn the courts of England and France, a rowdy Southampton tavern, the beseiged town of Harfleur and, with imaginative light projections as the sun sets over Guildford, the bloody battlefield of Agincourt. (Unexpectedly, on the night we were there, the heatwave over Guildford broke and for a moment we in the audience feared a reinactment ot the stormy night of the battle of Agincourt, but it passed quickly over.) True to the narrative thread in the play, we are urged to walk the few steps to each scene by the actors themselves. In Shakespeare’s wonderful lines we’re exhorted to visualise stormy seas, creaking rigging, cold fearful dawn and raging battlefield. These poetic interjections ‘breaking the fourth wall’ are one of the most engaging aspects of the play. King Henry is played magnificently by Gavin Fowler, with dignity and passion as he sets out his leadership plans, with humility as he moves among the common soldiers incognito, with ferocity as he threatens Harfleur, and with charm as he woos Catherine, the French princess through whom he seals peace between France and England. He’s also hilarious as a drunken bawd in the tavern scene. Sarah Gobran, playing a range of male characters including the King of France, is alternately regal and measured, fierce and vengeful, treacherous and loyal, always convincing. Matt Pinches succeeds in portraying the effete arrogance of the Dauphin, the oily pomposity of Bishop of Canterbury and making the audience howl with laughter as a drunken soldier of fortune in the tavern scene — his antics with Pistol, Bardolph and the other ruffians are absolutely priceless. Will Arundell’s performance as Pistol and other tough characters on both sides of the channel is taut and energetic, driving scenes of conflict with precision, ferocity and flair. Nikita Johal is effective as chronicler and councillor, and very funny when as Princess Catherine she tries to learn English under Matt Pinches’ guidance as Alice, her lady-in-waiting. This review was first published online in Essential Surrey

CYRANO DE BERGERAC

Adapted by Glyn Maxwell from the play by Edmond Rostand Guildburys Theatre in Merrist Wood 19 – 22 July 2023 Most people have heard of Cyrano de Bergerac, the 17th Century character who was known for his enormous nose, but I for one didn’t realise that he was a real person, not a character from romantic fiction. For their Picnic Theatre in Merrist Wood this year, Guildburys have chosen to enact a story of unrequited, unselfish love, bravery, legendary swordsmanship and literary talent that was written about him by Edmond Rostand 150 years later — and what a tour de force they’ve made of it! We fall in love with Cyrano as he quips his way through the hypocrisies of church and state, fights a hundred duels simultaneously, and answers with cutting wit the taunts and cruel jokes his rivals make about his enormous nose. Despite his less than romantic appearance he writes his way into the arms of his childhood love. He dies, aged only thirty-six, by an unknown hand. The historic Cyrano was a poet as well as a playwright, a satirist and an outspoken critic of the church and the aristocracy, who made many enemies. He fought in the French army in the Siege of Arras in 1640. Glyn Maxwell, himself a poet, has adapted Rostand’s play to emphasise the literary element in the real Cyrano’s life, and we chuckled at the many jokes he includes about the status of the poet in society, then and today. Duelling with words as well as swords, Cyrano withstands all criticism of his looks but yearns to be loved by Roxane, his cousin, who loves a more handsome, rather inarticulate soldier, Christian (Gabi King). To help them both, and protect her from Count Antoine de Guiche, the (initially at least) dastardly aristocrat claiming droit de seigneur from Roxane, Cyrano writes poems for Christian to enable him to woo Roxanne, but when he tries to teach his friend to write poetry himself, the results are hilarious. Paul Baverstock’s performance as Cyrano is brilliant: he electrifies the atmosphere with his boldness and his throwaway delivery of witty riposts. The ensemble performances are very strong too. Richard Walter plays the Parisian pastrycook Ragueneau, jovial, larger than life and dispensing cakes to the down-at-heel poets who are Cyrano’s supporters and the motley group of Gascoigne Cadets. Amie Felton portrays Roxane as a giggly airhead craving flattery in poetry, and Neil James as Count Antoine bears an uncanny likeness to Jacob Rees- Mogg in the first half of the play — he relaxes into a more respectful equal of Cyrano in the second half — another memorable performance. This is a wonderful evening of theatre in the romantic woodland outside Merrist Wood House. We laughed, we almost cried, and we learned — what more could we ask? Guildburys have again chosen and performed a play full of surprises, inventive direction and brilliant performances. This review was first published online in Essential Surrey AROUND THE WORLD IN 80 DAYS

Merrist Wood, Guildford 13th – 16th July 2022 5 STARS The Guildbury’s open-air production based on Jules Verne’s fantasy/adventure novel is a miracle of invention and wit. With only his powerful faith in Bradshaw’s Railway Guide (the Bible of Victorian travellers) £20,000 in cash and his faithful manservant Jean Passepartout, Phileas Fogg, a rich, routine-bound business man, sets off to win a wager and prove to his friends that he can travel round the world using steam and locomotive power (there was no air flight at the time, despite the 20th century Disney movie of the story). There are many complicated diversions en route, and a surprise at the end. A huge undertaking — almost equal in its demands to those met by Eddie Woolrich, Guildbury’s director of this adaptation for the theatre by American playwright Laura Eason. Wisely following her advice on staging such a long and eventful journey, he creates London, Paris, Brindisi, Bombay, Hongkong, San Francisco and the boats and trains (and an elephant) between them in true theatrical style. They’re conjured up using the simplest of props, the most assured acting and the wittiest stage-management. The two main characters are brilliantly brought to life by Richard Copperwaite as Phileas Fogg and Joe Hall as Passepartout. Written by a Frenchman, Phileas Fogg is a parody of British 19th colonialism: pedantic, stiff, humourless, arrogant, prejudiced and blinkered to all but his goal to succeed — but not totally immune to modifing his outlook through encounters with the world outside Britain. Copperwaite carries this role off with tremendous commitment, contrasting perfectly with Joe Hall’s Passepartout, who is the archetypal opposite, always open to new encounters and experiences, and easily distracted! Joe’s performance as a victim of a Chinese drug den is priceless, as are his rash interventions when his master is threatened, and his gormless bewilderment in other tight spots. Jonathan Arundel as the bungling Scotland Yard detective following Fogg is a great parody of the English — always sportingly admitting ‘I deserved that’ when he’s knocked down by Passepartout! — and Amie Felton as Mrs Aouda the Indian widow whom they rescue in Bombay is suitably mild-mannered. The ensemble company give tireless support to the central characters, as gentlemen, citizens of the various cities they visit, sailors, ruffians and bureaucrats and consuls. There are wonderful moments of comedy and wit. The elephant ride stands out for me, as does the ‘human pyramid’ that Passepartout demonstrates as a circus performer. The fight scenes are great, and Fogg becoming ‘man of action’ in a storm at sea is memorably funny. I loved a brief witty reference to the red hot-air balloon of the Disney film, too. In one of the hottest July weeks of this century, we picnicked, laughed and thoroughly enjoyed this immersion in true theatre. There may be some tickets left — why not grab some of them and journey to Merrist Wood grounds this week to join in the fun? Tickets: https://www.guildburys.com/guidburys-picnic-theatre-around-the-world-in-80-daysjuly-13-16/  ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ — Guildford Shakespeare Company Rack’s Close, Guildford, 16th June – 2nd July 2022 Five stars A magical feast of fun and laughter — GSC does it again. ‘If you go down to the woods today…’ you won’t find bears as in A A Milne’s song, but you will find magic all this month. Rack’s Close, Guildford’s best-kept-secret forest, is the venue for the GSC’s latest production. On an idyllic Midsummer’s Day eve we were absolutely enchanted by this scintillating ‘Midsummer Night’s Dream’, directed by Abigail Anderson. Anderson writes that she aims to make the story ‘clear and exciting’, and she succeeds superlatively. I’ve seen many productions of the ‘Dream’, but never been engaged so fully from the outset with the personalities and motivations of the characters in this fast-moving, farcical and intricate plot. In Scene I the exposition of the four young lovers’ relationships and problems is achieved speedily and dramatically, and Helena (Annabelle Terry) makes her stormy entrance, foreshadowing even more furiously feisty behaviour when the four become hopelessly entangled under the influence of the magic drugs of the spirits of Nature in the forest beyond Athenian civilisation. This is followed up immediately by the introduction of the Mechanicals, who provide Shakespeare’s satire on literary romantic love and the world of play-writing and production —'Pyramus and Thisbe’ — and the iconic character of Bottom the weaver (Rosalind Blessed.) We in the audience loved being cast as potential actors and cheered with the rest when Snug (Dewi Mutiara Sarginson) sat next to us and was chosen to play ‘Lion’ (later in the play the Lion was quite a star!) The main theme is the madness (and comedy) that romantic love can lead to when human society’s expectations are overturned by natural impulses (personified by the fairy court’s interference with human relationships in the forest on the magic night of Midsummer.) In Anderson’s production this modern interpretation of the reality of magic and the supernatural world is beautifully balanced with the beliefs of the 16th Century in magic, spells and sprites. The whole cast is brilliant: I’d single out for special mention the outrageously funny Bottom played with huge gusto by Rosalind Blessed; Annabelle Terry, the dangerously scorned Helena (and the hilariously assertive Wall); and Daniel Kriler, a mischievous Puck who ‘puts a girdle round about the Earth’ using some intriguing modes of transport. ‘Pyramus and Thisbe’ is always a comic highlight, and is so in this production, but it takes a fresh approach to bring to the climactic fight among the four young lovers the kind of knockabout comedy we saw in Rack’s Close this evening —they literally ‘tear strips off one another’! Matt Eaton’s inventive soundscapes included invisible munchkin fairies (perhaps unfairly making Shakespeare’s incantations rather hard to follow) and a very convincing dawn chorus. ‘Albion’ by Mike Bartlett

The Guildburys at the Electric Theatre, Guildford 23rd —26th March 2022 The Guildburys carry off a complex performance: more than social comment, this is an evening about romance, loss and reality. In Albion Mike Bartlett adopts a Chekovian approach to plot and emotional theme, reminiscent of The Cherry Orchard, where a rural setting and its inhabitants are portrayed with an allegorical undercurrent. We meet Audrey Walters (Cheryl Malam), a wealthy middle-aged entrepreneur who has bought a stately pile fallen into disrepair, and who is determined to restore its gardens to the glory that she remembers from her childhood, when she spent idyllic holidays there with her uncle, who then owned it. She expects her weak, complaisant husband Paul (Jonathan Constant) and her disaffected teenaged daughter Zara (Sophie Walker), to fall in with her plans without compromise. Paul loves her enough to comply; Zara longs to be free to grow, and to return to London. Consultation is foreign to Audrey’s modus operandi; this character is consistently strident, self-centred and unempathetic towards everyone around her, including Anna, the partner of her dead son. She destroys Zara’s self-esteem and creative aspirations along with the girl’s lesbian affair with her own old friend, Katherine (Gilly Fick). Her single-minded fixation on her vision of a vanished past takes priority over all other considerations: she is willing to sacrifice all else for it. The play was first performed in 2017, during the hiatus between the Brexit referendum and subsequent diplomatic negotiations aimed at fulfilling the ‘Leavers’ dual aspirations to ‘restore’ British culture to the status of an imagined historical ideal and at the same time to create vibrant change. Audrey’s garden project results in her alienating everyone close to her (except Paul) as well as her neighbours in the community, through her selfish, possessive and ungenerous behaviour. But if you’re expecting overt political comment, you won’t find it here. I came away from this complex play with the sense that it was a portrait of a central character embodying much of the worst of English moneyed class entitlement and arrogance, who spreads destruction while believing that she is being creative. Loss, grief and broken relationships result from her inability to consult with others or to accept changes that are beyond her control. In the dialogue there’s wit and telling references to the realities that Audrey’s rigid mindset is discounting: for example, climate change means the garden’s flower beds can’t be restored to their original plan; her son’s death in Afghanistan, which she frames as a glorious patriotic sacrifice, is seen to have been pointless in the light of subsequent events there. Cheryl Malam sustains stridency and controlling self-possession throughout the play; it is hard to feel sorry for Audrey when in the last scene she insists that she will ‘go on’: we see how her attitudes will lead to further losses and alienations. However much we dislike her, she is a tragic hero in the dramatic sense. Jonathan Constant lends an endearing mildness and humour to the character of Paul. As the two ‘old retainers’, Barbara Tresidder and Kim Fergusson lighten the relentlessly tense atmosphere among the family members; Claire Howes as the bright, assertively self-confident Polish cleaner/entrepreneur is an effective foil for Audrey’s self-indulgent romanticism and Zara’s unhappy search for a meaningful role in life. Gilly Fick is colourful and strong as Katherine, Audrey’s old friend who offers Zara a role as a creative lesbian partner and whom Audrey forces to her will —and loses. Janice Dempsey Hamlet by William Shakespeare — Guildford Shakespeare Company

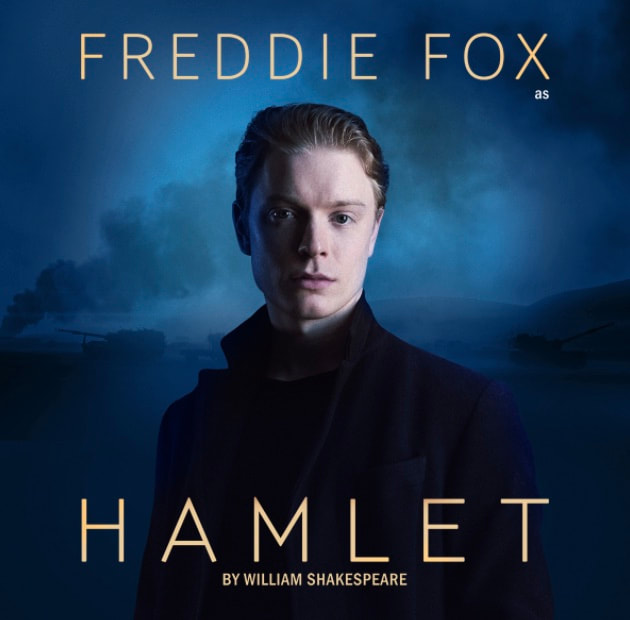

Holy Trinity Church, Guildford until 23rd February 2022 Freddie Fox is a dynamic, volatile Hamlet — a wonderful evening of theatre in an amazing setting. GSC are renowned for their productions in places other than purpose-built theatres, and with this month’s production of Hamlet they have again rendered the lack of a ‘home’ theatre a positive asset to their creativity. Holy Trinity Church in Guildford High Street becomes the stage on which Hamlet, Prince of Denmark struggles with his grief, his hatred for his murderous uncle Claudius and his disgust for his mother who has married her brother-in-law, a disgust which leads to his rejection of Ophelia and his accidental killing of her father, and the final complex denouement that leaves four characters dead onstage. Holy Trinity’s beautiful interior is enhanced by imaginative lighting by Mark Dymock that creates ghosts, battles and the castle of Elsinore with minimal need for props. Directing the play, Tom Littler says that he set out to use all the opportunities that a church building offers, and this includes live music, which is woven throughout the play: organ music; the cello, played beautifully by Rosalind Ford as Ophelia; and even a recorder played ironically by Hamlet like a penny whistle, as well as exciting thunderous and atmospheric sound effects designed by Matt Eaton, that hold together the fabric and changing moods of the scenes. Freddie Fox’s interpretation of Hamlet, the Prince of Denmark, is febrile, passionate, ironic, brooding and ferocious by turns. He dominates the stage and the rest of the cast, whenever he appears. His delivery of the memorable speeches is intense and powerful: even that old chestnut, ‘To be or not to be’, comes alive in his mouth. We believe in his suffering and understand his cause. Equally strong is Rosalind Ford as Ophelia. Her stage presence is as powerful as Hamlet’s; her depiction of Ophelia’s descent from elegant self-possession into madness and suicide brought tears to my eyes. Claudius (Noel White) is somewhat overshadowed by his angry nephew and appears as a rather weak character who depends on tricks and schemes to seize and hold on to power; Gertrude (Karen Ascoe) seems less in love with him than some productions would have us believe; Horatio, Hamlet’s friend, is played by Pepter Lunkuse: the casting of so feminine an actor somewhat weakened the character’s role, I felt. Edward Fox (Freddie’s real father) plays the ghost of the dead King Hamlet as a disembodied voice over an evocative light display that changes the church’s furniture into flickering, supernatural images. This was a brilliant piece of theatre. Other original moments are provided when Hamlet, pretending madness, appears in a bishop’s costume intoning nonsense from the (real) pulpit, and the reduction of the ‘play within the play’ to a few moments of flickering blue light shone from behind the audience —only the reactions of Claudius and Gertrude, sitting on the stage, show what they’re watching. This is an exciting and original production of Hamlet. It’s on until 23rd February — seats are reduced In number for pandemic reasons, so book your ticket as soon as you can. As You Like It’ by William Shakespeare

Guildford Shakespeare Company Racks Close. Guildford, 19th – 31st July 2021 What a pleasure to sit in a lush clearing in Rack’s Close woods as the sun goes down, the lights go up on actors’ expressive faces, and Shakespeare’s timeless comedy of love at first sight plays out under towering trees. The Guildford Shakespeare Company has struck gold with their ‘As You Like it’ this week. Some of Shakespeare’s most memorable speeches shine like jewels in this plot of warring brothers and a cross-dressing maiden, spiced with glorious comic business by all of the cast. The eight members of the company between them play fifteen characters, and with brilliant direction they carry all of them off con brio. Given that the plot involves peremptory exile by the absolute authority of a ruler, the setting of this production in the authoritarian state of Germany in the 1930’s makes sense. Matt Pinches is very much at home as Touchstone, a Weimar cabaret clown for most of the play, scoring points, flouncing, teasing and occasionally sulking hilariously, in black tights, tinsel mini-skirt and red high-heels. As Jaques, the philosopher in the forest community, Sarah Gobran’s moving delivery of the famous speech known as ‘The Seven Ages of Man’ holds us spellbound. She’s terrifying as the cruel Duke in the first act, and comically charming as Phoebe, a shepherdess who falls in love with Rosalind thinking she’s a boy. Tom Richardson, as Phoebe’s rejected swain Silvius, is lovably gullible, and Corey Montague-Sholay as the other bucolic lover, Audrey, brings out all the comic potential of his rustic overalls when he’s teased by Touchstone. Rachel Summers and Natasha Rickman bring giggly girlishness to the roles of the two best friends, Celia the Duke’s daughter and her cousin Rosalind, who run away together to the forest after the Duke throws Rosalind out. Comparing notes about boys, they fill the woods with their enthusiastic screams, see-saw moods and lively scamperings. Natasha Rickman with Rosalind’s passionate, barely held-back longing creates a steamy connection to James Sheldon’s confused Orlando who believes she’s a boy. Her comic timing is faultless. Robert Maskell’s accomplished performances as the banished Duke Senior and separately as Corin, the shepherd who tries his wit against Touchstone, are very engaging: he brings both joyfully to life. Memorable moments include the scene when Rosalind, still disguised as a boy, tells all the tangled would-be lovers that they will be married tomorrow but she herself ’will marry no woman’ — the choreography of this scene is irresistibly funny. Don’t miss this wonderful chance to enjoy live theatre in a beautiful glade — The Guildford Shakespeare Company have again filled warm summer evenings with laughter and magical art. Tickets and information about the cast are here. This review was first published by Essential Surrey online magazine https://www.essentialsurrey.co.uk |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed